April 26, 2019 - Comments Off on Managing Your Design Feedback

Managing Your Design Feedback

Feeling defensive towards feedback can be a natural response. Work you’ve put hours into is being criticized by people who don’t have your same level of context or project knowledge. It’s easy to take this feedback personally (they don’t like me, so of course they’re tearing up my work) but listening to and processing someone’s feedback is a valuable exercise in patience, empathy, and understanding that may ultimately make you a stronger collaborator.

1. Separate your self-worth from your feedback.

When someone gives you feedback, in return, give them the benefit of good intent. Trust that it takes courage to give and get feedback and the people who invest their time into you are doing so for your (or at least your project’s) benefit. This perspective will allow you to adopt a growth mindset.

In her post, Taking Feedback Impersonally, Facebook’s VP of product design, Julie Zhuo references a growth mindset as a way of separating your self-worth from the feedback you receive: “With a growth mindset, you start to crave feedback from as many people as possible, even critical feedback, because you realize it’s the fastest way for you to learn and improve.” When you’re able to separate feedback from your ego, your vulnerability will allow you to become more willing accept criticism and new ideas.

As a residence hall advisor in college, I recited a phrase I had learned from one of my advisors: “It’s not you, it’s what you did.” While not completely similar, this mindset of separating an actor from their action is one way to mentally unpack the process of receiving feedback for your work. The feedback is a response to what you’re presenting. Not you, yourself.

This principle is challenging for anyone whose passion is their profession. Many designers feel that their identity is design. If you don’t like my design choices, you don’t like me as a designer. Who you are, what you do and how you do it are not intrinsically linked.

2. Understand your feedback by asking questions.

When receiving feedback, it’s tempting to respond with a quick defense of your rationale. While legitimate, this call-and-response can easily become a battle of egos — ultimately failing to benefit the project nor your relationship with that person. Navigating how to tactfully handle a critique can sometimes feel like a game of chess. What should I say to represent my point while respecting the feedback I just got? How do I disagree with everything this person just said?

There are times you’ll undoubtably need to set things straight. Maybe a suggestion is made that’s out of scope or unrelated to your project’s objective. Not all feedback is good feedback and for the sake of time and focus, you’ll want to help guide the conversation to remain on-track to solve the problem at hand.

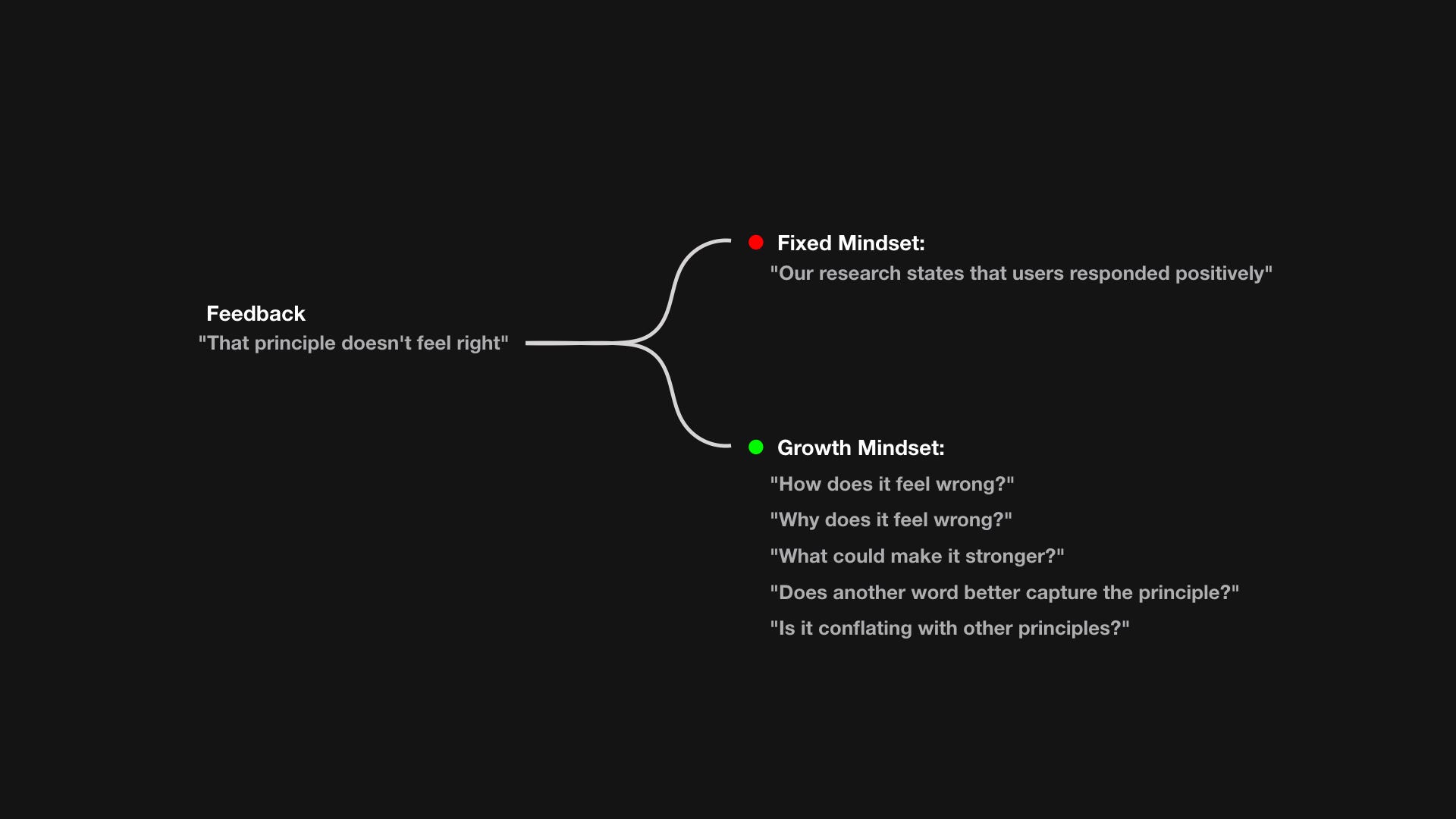

Being said, there’s a difference between feedback that’s unfocused and feedback you simply disagree with. For the ladder, first question why this is the feedback you’re getting. Ask questions that can help you dig further to address underlying issues that may uncover larger problems.

A discussion-focused dialogue will help weed out “ego-driven” feedback while preserving legitimate concerns. Feedback that’s simply based on a subjective feeling can easily fall apart when you take time to dig into wherever it’s coming from. “I’m not a fan of that color,” (besides not being constructive) doesn’t carry depth. When getting these kinds of statements, respond with probing questions that will prompt the feedback giver to open up about their concern. Start questions with how, what or why to allow for a more open dialogue.

By using a questions-first method, you’ll allow the feedback giver to fully explain where they’re coming from and why they have their concern. Like the rules of a courtroom, critique should give an opportunity for both sides of a case to make their arguments.

3. Focus on feedback collection. Not action.

Gathering feedback is your chance in the creative process to collect the responses you need to move forward. It’s not the time to act upon the given feedback. One thing I see a lot is live-problem solving. Someone will be getting feedback and in response, they’ll open up their design app (as someone’s still talking to them) and start fiddling with their designs—then turning to the feedback giver, they’ll pose the question, “Okay, so you mean like this?”

While it’s tempting to immediately address the problem, live-editing is not a valuable use of time for anyone. When this happens, the giver of the feedback isn’t being fully listened to and the receiver isn’t fully processing the problem. This makes the designer appear like they want to be done by taking the quickest path via minimal investment. The identified issue might get solved in this rapid-fire exchange, but it’s not sustainable for all feedback and builds a poor habit of impulsive action based off half-baked ideas.

Instead, collect. Use your time to understand the issues that are being raised by your team members. Lessen your burden by not assuming the role of defender and immediate-responder. This is your time to be a listener. Collect the social temperature of your work, gather concerns and learn about resources that may help you move to the next step of your process.